Gallberry, photographed at Frenchman's Forest Natural Area, Palm Beach Gardens, Palm Beach County, in April 2018.

If Gallberry, Ilex glabra, didn't exist, it would have to be invented. It's that important to the natural scheme of things. As many as 15 species of birds eat the fruit, while others find cover within its limbs. And gallberry holds both its fruit and leaves through the winter, when both commodities are in short supply.

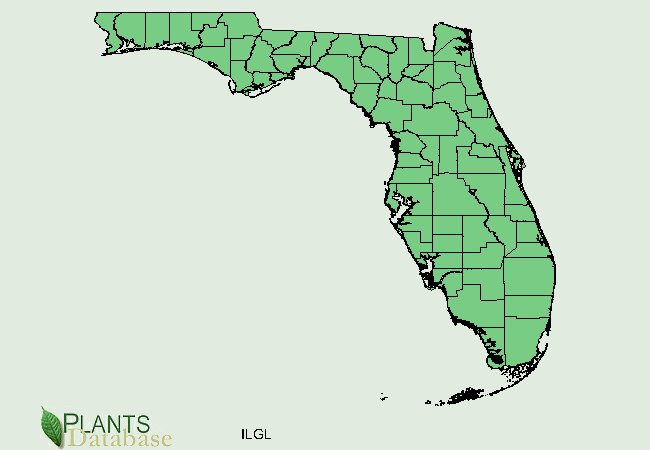

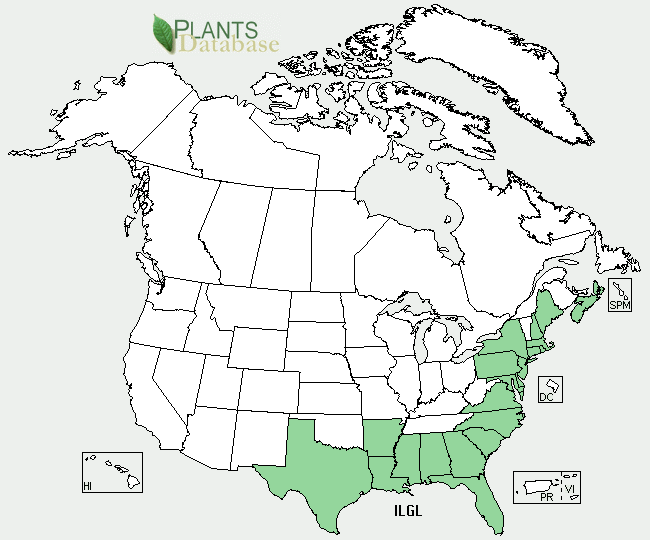

Gallberry is a member of the holly family and a widespread member at that, found in all 67 Florida counties and along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts from Texas to the Maritime provinces of Canada. Its natural range includes a few places inland, including Pennsylvania (where it's believed to be extinct) and Arkansas. It has a host of common names that give you an idea of how widespread it is: inkberry, bitter gallberry, winterberry, Canadian winterberry, evergreen winterberry and Appalachian tea are a few.

A quick glance and you might miss the resemblence to the holly family, but look closely and you can see it in the small points that occur along the edges of the leaves. And like other members of the family, it is dioecious, meaning male and female flowers are found on separate plants.

Gallberry is a shrub, grows to about eight feet high and can form dense thickets, spreading via rhizomes, or underground stems. It blooms in late winter into spring, and produce a reddish-black berry (technically called a drupe) that is an important food for mammals and birds, which do inkberry a solid in return by dispersing its seeds. Female flowers appear singly, male flowers in small clusters of between three and seven. They are a kind of white to yellowish green and won't exactly dazzle the eye of the beholder. Leaves are stiff to the touch, alternate along the stem and are either entire (smooth along the edges) or have those fine mini-holly-like points. Gallberry remains green year-round, even in the frigid north, and holds its fruit into the winter.

Marsh rabbits and deer not only find cover in gallberry's dense foliage, they also eat the leaves. Gallberry's fruit isn't edible for us humans, but those leaves allegedly make a fine tea when dried and roasted. During the Civil War, Confederate soldiers used inkberry as a coffee/tea substitute. Tastes like orange pekoe, and has the added bonus of being caffeine free (unlike its cousin, yaupon holly, which has the highest caffeine content of any plant in North America). Gallberry is found in moist to wet sites, including wet pinelands and pine barrens, wetlands, swamps, along lake and pond edges and creek bottoms. Inkberry will grow in full sun but it also can take some shade. Those spreading rhizomes also protect the plant against fire; a single blaze might top kill the plant but it most likely will sprout again in a matter of months.

Gallberry is highly valued in landscaping, because it is evergreen and holds its fruit, which add visual interest in winter. It is used as an accent plant — some say it's perfect for that place where the air conditioner drains — and in natural and restored landscapes. It's also grown by bird lovers looking to attract their feathery friends. It does have drawbacks — it tends to thin out toward the ground as it grows and there is its tendency to spread. But there are cultivars commercially available that reduce the negatives.

Gallberry is a member of Aquifoliaceae, the holly family. Note: gallberry is often referred to as inkberry, which can refer to another plant found in coastal South Florida. To reduce confusion, we've used gallberry here, but if you do any research on it, scientifically it's always Ilex glabra.

Click on photo for larger image

U.S. Department of Agriculture Distribution Maps