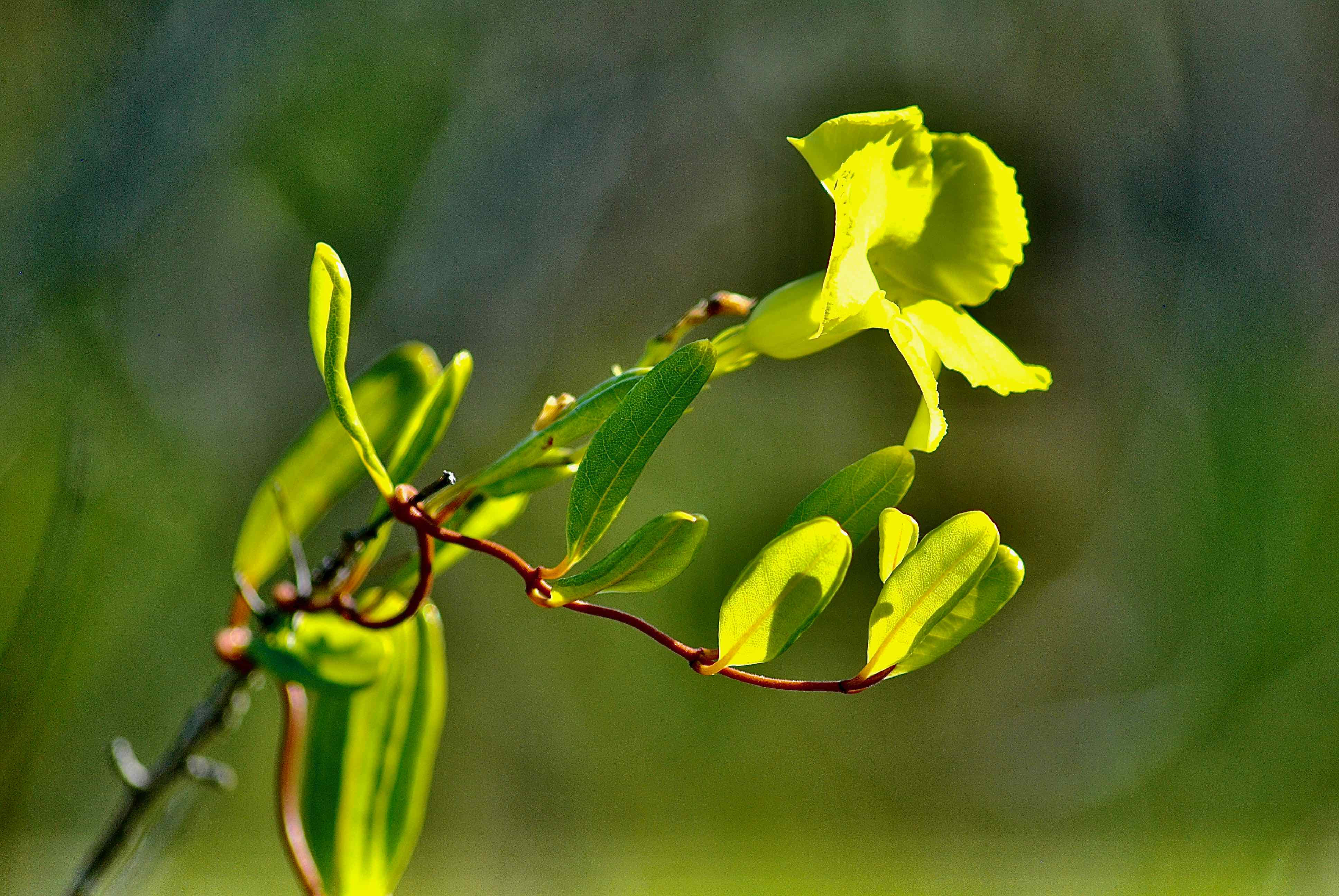

Pineland allamanda, photographed at Big Pine Key, Key Deer National Wildlife Refuge, Monroe County, in December 2013.

Pineland Allamanda, Angadenia Berteroi, is a plant so rare nobody knows exactly how rare it might be.

It is rare enough to be listed in Florida as threatened, as in threatened with extinction, but its range extends through much of the northern Caribbean, where there's not much information on how strong the population might be. Because of the scarcity of data about the plant beyond Florida's borders, pineland allamanda is considered vulnerable to extinction.

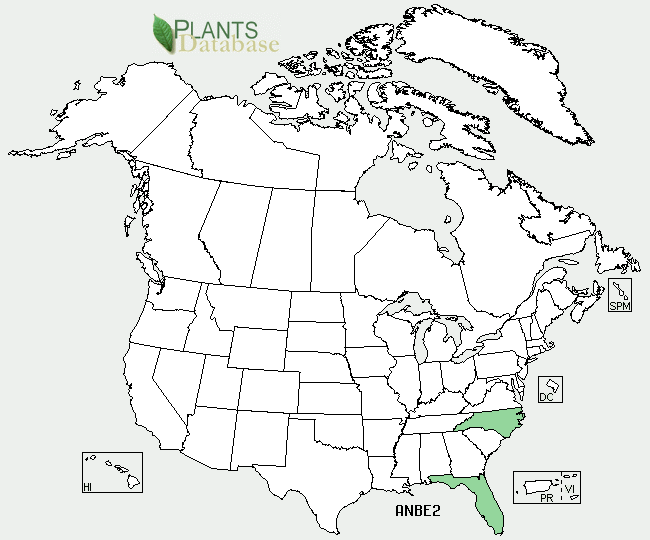

It is a Florida native, but its range in the Sunshine State is limited to Monroe and Miami-Dade counties. The U.S. Department of Agriculture also says pineland allamanda is a native of North Carolina, but some say that's unlikely given the huge geographical gap involved. More likely, it's theorized that someone planted pineland allamanda, which then escaped into the wild and then died off. Also within its range: Cuba, Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and the Bahamas.

Pineland allamanda itself looks like a miniature version of the allamanda that might be found in the nursery department of a home center. It can be a "subshrub" in habit, growing six to 18 inches tall, or it can be a clambering vine, reaching perhaps three feet in length. It is drought tolerant and grows in full sun or part shade. Favorite habitats include rock pinelands, naturally, and marl prairies. It is a perennial.

The most outstanding feature of the plant is its flowers, which are mostly a bright yellow but also can be a subdued cream-color. They bloom year round, eventually producing a slender seed pod as its fruit. The leaves are arranged opposite each other along the stem, oblong in shape, leathery in texture, with an edge that is smooth but curled.

One major reason why pineland allamanda is so rare might be because it puts out relatively few fruit. According to a study done by two Florida International University researchers and published by the International Journal of Plant Sciences in 2010, the flower are structured in such a way as to discourage cross pollination — pollination with itself or related plants — and encourage outcross pollination — pollination from unrelated plants. The researchers concluded that the low rate of fruit-setting might be due to either low visitation rates by pollinators, pollination with closely related neighbors or both. As a result, pineland allamanda flowers set relatively few fruit, which means few seeds and few offspring.

Which brings us to this: the general assumption has been that pineland allamanda is pollinated primarily by moths, particularly the polka-dot wasp moth and the oleander moth, both of which use the plant as a host for their offspring. However a study done some years ago by Beyte Barrios Roque a Ph.D candidate at Florida International University, found that while other pollinators such as skippers and butterflies more frequently visited pineland allamanda flowers, it was two species of bees that actually did more of the heavy lifting, so to speak, when it came to transferring pollen from one plant to another.

Part of the problem for the plant is its dependence on the rockland habitats found in Miami-Dade and Monroe counties. Pine rockland habitats need periodic fire to prevent small, hardwood trees from transforming the area into something hammock-like, which pineland allamanda can't tolerate. Fire also reduces the amount of leaf litter on the ground keeping the chemical composition of the soil favorable for germination of pineland allamanda seeds. But little pine rockland remains outside the protected confines of Everglades National Park. And what little does remain, are mostly small, scattered fragments many in urban settings, where wild fires are rare and prescribed burns difficult to conduct. The same paper by Roque found that pineland allamanda does best on larger fragments and on fragments that are close to others. Remember, in order to reproduce, it needs pollen from plants that aren't closely related genetically, so it needs to be close enough to these nonrelatives that pollinators can frequent both populations.

Back in the day when pineland allamanda was a bit more plentiful than it is today, the Seminoles would use the root to make a wash to treat skin sores and chronic sicknesses. It was also used to treat something called menstruation sickness, the symptoms of which included stomach pain and impotence in men. In the Bahamas it was used to ward off "intercourse taboo." The sap of the plant is both an eye and skin irritant, however.

Pineland allamanda is also known as pineland golden trumpet, liceroot and wild liceroot. It is a member of apocynaceae, the dog bane family. One final note: the name berteroi honors 18th century Italian botanist Carlo Luigi Bertero.

U.S. Department of Agriculture Distribution Maps