Virginia creeper, photographed along A1A, Palm Beach County, in June 2017.

If you Google Virginia creeper, Parthenocissus quinquefolia, you'll come up with numerous hits telling you how to kill this vine. Any plant growing in the wrong place can be a pest, and Virginia creeper can be a real pain in the butt if it's growing on your home, a wood fence or lacing itself in your hedges.

But we'd argue that with Virginia creeper, the positives outweigh the negatives, especially when it's growing out in the wild.

Virginia creeper is fairly attractive. Songbirds love the berries it produces, as do squirrels, deer and other animals. Deer and cattle will browse the leaves and stems. But this Florida native is also fairly aggressive almost to the point of being invasive. It is a vine that can reach massive lengths, able to grow on and stick to just about any surface — walls, fences, trees, your house — thanks to tendrils that have adhesive disks on the end. Think twice before letting it grow onto your house because, we can tell you from experience, that it is difficult to remove. Oh, the plant will come off, but those pads remain.

Virginia creeper is grown as a ground cover, as an ornamental and to attract wildlife. Because of its aggressive growth and dense foliage, it's also used to hide unsightly things like rock piles and tree stumps. By the way, some people will mistake Virginia creeper as poison ivy, but the two are easily distinguished from each other; both can have woody stems, both are aggressive climbers and both have compound leaves. The difference? our guy has five leaflets; poison ivy has three. Leaflets of three let it be.

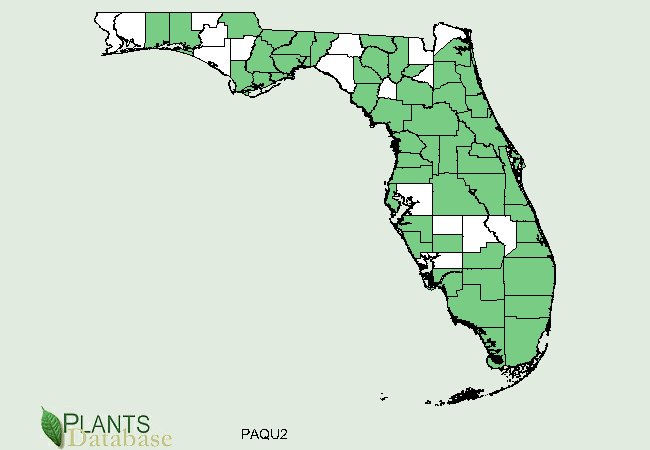

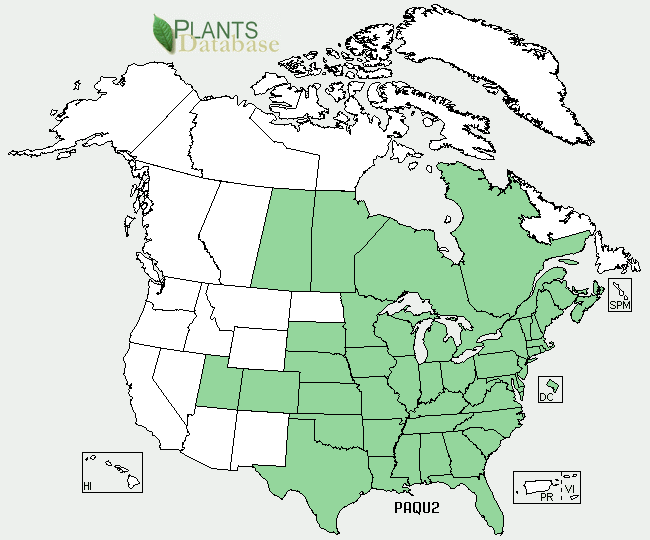

Virginia creeper can grow to 60 feet or more. Its native range includes most of the eastern and central United States, extending westward into Colorado and Utah. It's found as far north as Canada and as far south as Cuba and the Bahamas.

It is a fast-growing perennial that will trail along the ground or climb into the sky. The compound leaves have five leaflets, each two to six inches long and with serrated, or toothed, edges. New leaves are tinged red, turning green as they mature. In the northern parts of their range, the leaves will turn spectacular shades of red in the fall before dropping as winter approaches. In the south, the plant is semi-deciduous, dropping only some of its leaves. The vines turn woody as the plant matures, the skin brown and covered with small, raised dots.

Virginia creeper blooms in the spring; the flowers are small, greenish white and grow in clusters. Fruit follows in summer into fall, first a pale color but turning blue to near black when ripe. The fruit is a delight for birds and other animals but is toxic and potentially deadly for humans. The sap can irritate the skin. Native Americans have used Virginia creeper to make medicines and dyes and as a food. The Kiowa used it to make a pink dye for war paint, while the Iroquois used it to counteract the effects of poison sumac. The Ojibwa boiled the root as a special food.

Fun fact: there are nine plants growing in South Florida that have Virginia as part of their name, all natives, some quite rare. Fun fact No. 2: there are 12,000 to 19,000 Virginia creeper seeds per pound. Fun fact No. 3: the genus name, Parthenocissus, is Greek for virgin ivy, while the species name, quinquefolia, refers to the plant's signature five leaflets.

Other common names include woodbind, American ivy, five-leaved ivy (also spelled fiveleaved), five leaves and thicket creeper. It is a member of Vitaceae, the grape family.

Photo Gallery — Click on photo for larger image

U.S. Department of Agriculture Distribution Maps