Cypress trees, photographed at Green Cay Nature Center, Boynton Beach, Palm Beach County, in April 2016.

Cypress forests once covered great swaths of Florida. They were ancient places, with trees almost monument-like, centuries old and standing 100 feet into the air and more. The old-growth forests are mostly gone now, the trees cut for lumber and to clear land for development. But the two species of cypress native to Florida, the bald cypress and the pond cypress, still dot the landscape and play vital roles economically and ecologically. Florida, in fact, has more cypress forest than any other state.

Both species are members of Cupressaceae, the cypress tree family, and both are members of the Taxodium genera. Ponds and balds are similar enough to each other that at one point they were thought to be one species. There are those who still maintain that the two are really one species.

Both are prized for their wood, which is insect and rot resistant, though bald cypress traditionally more so than pond. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, logging operations cut down Florida's trees in large-scale operations; in places like the Fakahatchee Strand, canals were dug to drain the swamp, roads and railroad beds were carved out of the forests, towns and mills were built to accomodate workers and cut logs into lumber. By the 1930s, the state led the nation in cypress lumber production. By 1950, most of the old-growth trees were gone. Fakahatchee is now a state park, the roads and beds now trails, the canals being filled in to restore natural water flow. Most of the old growth forests are gone, though there are remnants.

The wood was used for everything from making shingles to cisterns, water tanks, water pipes and buckets, which should give you a good idea how durable cypress is. Thing is, the really good stuff comes from trees centuries old. Lumber cut from younger trees isn't nearly as durable, despite some marketing claims. Today, cypress is logged for lumber as well as mulch. Both species are used in landscaping.

A cypress forest once spread between Lake Okeechobee and Fort Lauderdale that essentially created a border between the pine forests of the coastal ridges and the Everglades to the west. All of it is gone for lumber and development but for a few remnants, the largest of which is the 400-acre cypress dome preserved at the Loxahatchee National Wildlife Refuge west of Boynton Beach. And even that is secondary growth, with the trees between 50 and 60 years old.

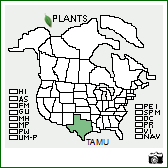

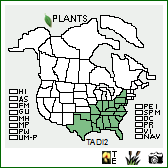

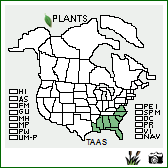

All in all, there are about 30 different genera in Cupressaceae, the cypress family, and as many as 140 separate species. Eight genera are found in the United States, including junipers, redwoods and sequoias. Florida's cypress trees are members of the genus Taxodium, of which there are three members, bald, pond and Montezuma, aka Taxodium mucronatum, which is found in South Texas into Mexico.

Cypress trees are conifers, with needles for leaves and seed-bearing cones. Both bald and pond cypress are deciduous, meaning they drop their needles in the fall. They also lose their chlorophyll, the chemical that makes green plants green, turning into yellows, oranges and browns that can last until new growth sprouts come spring. There are physical differences between the two species, especially the structure of the needles, as shown in the photos at left. Bald cypress grow faster and larger than pond. However, the differences aren't always clear, and adding to the confusion, the two species can hybridize with each other, producing trees with characteristics of both types.

Pond cypress trees are found in isolated, nutrient-poor depressions where the water is acidic; bald in places with running water, along rivers and streams where the soil is nutrient rich and less acidic. Pond cypress habitats may dry up several times a year and are susceptible to fire. Pond cypress bark is thicker than bald cypress and fire resistant.

Cypress trees are incredibly valuable to the environment. They can pull carbon dioxide out of the air and store it in huge quantities, a process known as sequestration. They improve water quality by removing phosphorus and nitrogen, control flooding and recharge ground water. They provide both food, shelter and habitat for a wide range of species, including birds and mammals. There are cypress dome swamps, places where decaying plant matter acidifies the water, which in turn creates a hole or depression by dissolving the limestone bedrock. Pond cypress trees grow in and around the hole, bigger trees toward the center, where growing conditions are most favorable, becoming progressively smaller smaller the farther out they grow, as nutrients and water become less abundant. Trees in the outter ring might be as old as trees in the center even though they might be a fraction of their size. The effect creates the illusion of a dome, hence the term. If you looked down on the dome, it would appear to be a donut, with the center clear of trees as the water becomes too deep for trees to grow. Cypress strand swamps are similar but are linear in shape, more like a trench than a hole. There are also cypress savannahs, where stunted pond cypress dot prairies of sedges and grasses.

They are slow-growing trees but they can live incredibly long — one tree in Central Florida named The Senator was estimated to be 3,500 years old before an arsonist burned it down in 2012. Its neighbor, known as Lady Liberty, is estimated to be 2,000 years old. The bald cypress trees of Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary are about 500 years old. The reason that there aren't older trees: a fire burned down the ancient forest that once stood there, according to the Audubon Society, owners of Corkscrew.

On both species, the trunks of the trees are tapered and buttressed — flaired supports at the base reminiscent of medieval cathedrals. The roots have knobs called knees that come out of the ground. Scientists aren't sure what they do, but theories include providing additional support in mucky soil, aerating roots and storing nutrients. Cypress will grow around objects touching them, including other trees, a response called thigmotropism.

Click on photo for larger image

U.S. Department of Agriculture Distribution Maps